All the major browsers shipped the native JavaScript modules support out of the box:

which means, the time we can use them without module bundlers/transpilers has come.

To understand better how we come to this point let’s start from the JS modules history and then take a look at the current Native ES modules features.

History

Historically JavaScript didn’t provide the modules system. There were many techniques, I would count the most typical of them:

1) Just the long scripts inside a script tag. E.g.:

<!--html-->

<script type="application/javascript">

// module1 code

// module2 code

</script>

2) Separating logic across the files and including them using the script tags:

/* js */

// module1.js

// module1 code

// module2.js

// module2 code

<!--html-->

<script type="application/javascript" src="PATH/module1.js" ></script>

<script type="application/javascript" src="PATH/module2.js" ></script>

3) Module as a function (e.g. a module is a function which returns something, self-invoked function or JavaScript constructors)

- an Application file/model to be an entry point for the app:

// polyfill-vendor.js

(function(){

// polyfills-vendor code

}());

// module1.js

function module1(params){

// module1 code

return module1;

}

// module3.js

function module3(params){

this.a = params.a;

}

module3.prototype.getA = function(){

return this.a;

};

// app.js

var APP = {};

if(isModule1Needed){

APP.module1 = module1({param1:1});

}

APP.module3 = new module3({a: 42});

<!--html-->

<script type="application/javascript" src="PATH/polyfill-vendor.js" ></script>

<script type="application/javascript" src="PATH/module1.js" ></script>

<script type="application/javascript" src="PATH/module2.js" ></script>

<script type="application/javascript" src="PATH/app.js" ></script>

After that community invented separate techniques to actually continue this separation. The main idea is to provide a system, which will allow you just to include the one link to the JS file, like:

<!--html-->

<script type="application/javascript" src="PATH/app.js" ></script>

and everything else went on the bundler side.

Let’s take a look at the main JavaScript modules tech standards:

Asynchronous module definition (AMD)

This approach is widely used together with RequireJS library and tools like r.js for building the result bundle. The common syntax is:

// polyfill-vendor.js

define(function () {

// polyfills-vendor code

});

// module1.js

define(function () {

// module1 code

return module1;

});

// module2.js

define(function (params) {

var a = params.a;

function getA(){

return a;

}

return {

getA: getA

}

});

// app.js

define(['PATH/polyfill-vendor'] , function () {

define(['PATH/module1', 'PATH/module2'] , function (module1, module2) {

var APP = {};

if(isModule1Needed){

APP.module1 = module1({param1:1});

}

APP.module2 = new module2({a: 42});

});

});

CommonJS

It is the base JS bundling for Node.js ecosystem. One of the main tools for building using it is Browserify. Noticeable features of this standard are to provide a separate scope for each module, which avoids unintentional leakage of global variables.

Here is the example:

// polyfill-vendor.js

// polyfills-vendor code

// module1.js

// module1 code

module.exports= module1;

// module2.js

module.exports= function(params){

const a = params.a;

return {

getA: function(){

return a;

}

};

};

// app.js

require('PATH/polyfill-vendor');

const module1 = require('PATH/module1');

const module2 = require('PATH/module2');

const APP = {};

if(isModule1Needed){

APP.module1 = module1({param1:1});

}

APP.module2 = new module2({a: 42});

ECMAScript Modules (aka ES6/ES2015/Native JavaScript modules)

Another standard came to us with ES2015. It brings the syntax and features community needs:

- separate module scopes

- strict mode by default

- cyclic dependencies

- you can split code easily following the spec

There are some loaders/compilers/approaches which support some of the systems or both of them, e.g.:

Tools

For today we got used to using tools to bundle JavaScript modules. If we are speaking about ECMAScript Modules, you can use one of the following:

- Rollup

- Traceur Compiler

- Babel, particularly ES2015 modules to CommonJS transform plugin

- Webpack 2 which also brings the Tree Shaking (unused imports removing)

Usually, the tool provides a CLI and/or ability to provide a config and bundle your JS files.

It gets entry point(s) and bundles your files, usually adding use strict and

some also transpile the code to make it work in all the environments you need (old browsers, Node.js etc.).

Let’s take a look at the simplified Webpack config, which sets the entry point and uses Babel to proceed JS files:

// webpack.config.js

const path = require('path');

module.exports = {

entry: path.resolve('src', 'webpack.entry.js'),

output: {

path: path.resolve('build'),

filename: 'main.js',

publicPath: '/'

},

module: {

loaders: {

"test": /\.js?$/,

"exclude": /node_modules/,

"loader": "babel"

}

}

};

Mostly the config says:

- Start from the

webpack.entry.jsfile - Apply Babel loader for all the JS files (means, the code will be transpiled depending on the preset/plugins + bundled)

- Put the result into

main.jsfile

In that case typically the index.html file contains the following:

<script src="build/main.js"></script>

And you app is using the bundled/transpiled JS code. That the common approach with bundlers, let’s take a look how to make it work in the browser without any bundlers.

Native and bundled modules differences

Let’s start from the native modules features:

- Each module has own scope which is not the global one

- They are always in strict mode, even when “use strict” directive is not provided

- The module may import other modules using

importdirective - The module may export bindings using

export

So far we haven’t faced big differences to what we got used to having with bundlers.

The big difference is in the way the entry point should be provided for the browser.

You have to provide a script tag with the specific attribute type="module", e.g.:

<script type="module" scr="PATH/file.js"></script>

This tells the browser your script may contain imports of other scripts and they should be processed accordingly. The main question which appears here is:

Why JavaScript interpreter cannot detect by itself if the file is a module?

Here is one of the reasons, modules are in the strict mode by default, classical scripts- no:

- let’s say the interpreter parses the file, assuming it’s a classical script not in the strict mode

- then it finds “import\export” directives

- in this case, it should start from the beginning to parse all the code once again in the strict mode

Another reason- the same file can be valid without strict mode, and invalid with it. Then the validity depends on the way it is interpreted, which leads to unexpected problems.

Defining the type of an expected file loading opens many ways for the optimizations (e.g. loading file imports in parallel/before parsing the rest of the file). You can find some examples used by the Microsoft Chakra JavaScript engine for the ES modules.

Node.js way to mark the file as a module

Node.js nature is different from the browsers and the solution of using <script type="module">

is not applicable there.

Currently, there is still a discussion regarding the appropriate way of doing that.

Some solutions were rejected by the community:

- adding

"use module";to every file - Meta in package.json

Other options were under the consideration (thanks to @bmeck for highlighting):

- Determining if the source is an ES Module

- New file extension for the ES6 Modules

.mjs

Each method has own pros and cons, looks like Node.js will take the .mjs approach.

Simple native module example

ok, first, let’s create a simple demo

(you can run it in the environments you have set up to test them).

So it will be a simple module, which imports an another one and invokes a method from it.

First step- including the file using <script type="module"/>:

<!--index.html-->

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<script type="module" src="main.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

</body>

</html>

Here is the module file:

// main.js

import utils from "./utils.js";

utils.alert(`

JavaScript modules work in this browser:

https://blog.whatwg.org/js-modules

`);

And finally, the imported utils:

// utils.js

export default {

alert: (msg)=>{

alert(msg);

}

};

As you might notice, we provided the .js file extension when used the import directive.

This is another difference with the usual bundlers behavior-

native modules don’t add the .js extension by default.

Actually, it means you have to provide the exact URL. And the main requirement is that the resource should have a proper MIME type (thanks to @bradleymeck for the correcting this).

Secondary, let’s check the scope of the module (demo):

var x = 1;

alert(x === window.x);//false

alert(this === undefined);// true

Third- we will check that native modules are in the strict mode. E.g. the strict mode forbids deleting plain names. So the following demo shows that it throws an error in the module script:

// module.js

var x;

delete x; // !!! syntax error

alert(`

THIS ALERT SHOULDN'T be executed,

the error is expected

as the module's scripts are in the strict mode by default

`);

// classic.js

var x;

delete x; // !!! syntax error

alert(`

THIS ALERT SHOULD be executed,

as you can delete variables outside of the strict mode

`);

Strict mode cannot be avoided in the module scripts.

Takeaways

.jsextension cannot be omitted (the exact URL should be provided)- the scope is not global,

thisdoesn’t refer to anything - native modules are in the strict mode by default (not needed to provide ‘use strict’ anymore)

Inline module script

As with classic scripts, you can inline the code, instead of providing it in a separate file.

In the previous demo you can just inline main.js directly into the <script type="module">,

which will result in the same behavior:

<script type="module">

import utils from "./utils.js";

utils.alert(`

JavaScript modules work in this browser:

https://blog.whatwg.org/js-modules

`);

</script>

Takeaway

- to execute a script or load an external file and execute it as a module use

<script type="module">

How the browser loads and executes the modules

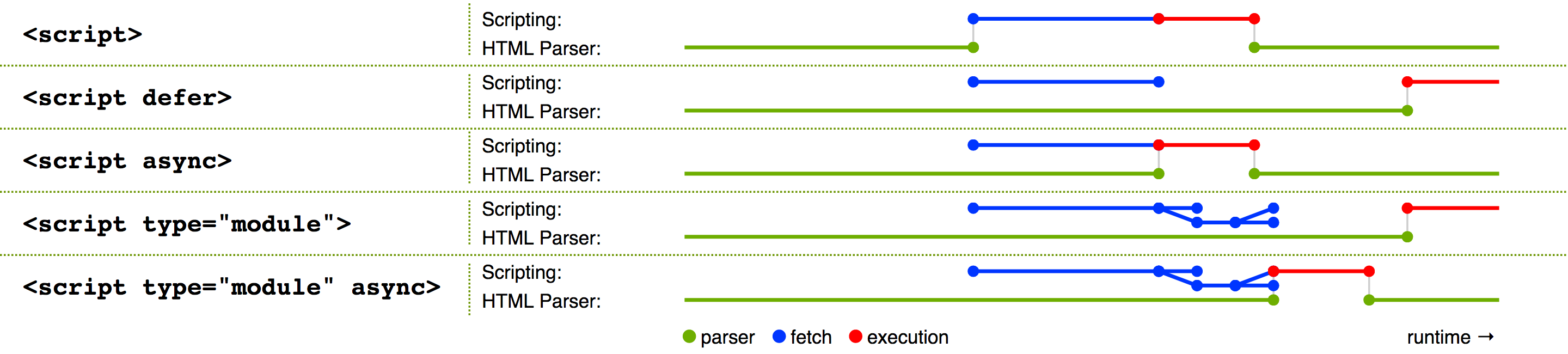

The modules are deferred by default.

To understand it, you can imagine each <script type="module"> has a hidden defer attribute.

Here is an image from the spec to explain this behavior:

It means, by default module scripts are not blocking, are loaded in parallel and are executed when the page has finished parsing.

You can change this behavior adding the async attribute, so the script will be executed as only it’s loaded.

The main difference in the default behavior with the classic scripts is that the classic scripts “are fetched and evaluated immediately, blocking parsing until these are both complete.”

To represent it, here is the demo with the script options,

where the first will be executed the classic script without the defer \ async attributes:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<script type="module" src="./script1.js"></script>

<script src="./script2.js"></script>

<script defer src="./script3.js"></script>

<script async src="./script4.js"></script>

<script type="module" async src="./script5.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

</body>

</html>

The others order depends on browsers implementation, size of the script, number of imported scripts etc.

Takeaways

- module scripts are deferred by default

Read more in the next article

It was a long journey till JS started to have own modules system, so we are coming into an era where they will be supported in the browsers natively and their usage will be inescapable.

That’s it for the first acquaintance with the native ECMAScript modules.

You can read about the differences between the ES and bundled modules, abilities to interact with the module scripts, tips, and tricks in my next article Native ECMAScript modules: the new features and differences from Webpack modules.

P.S.:

Honestly, when I tried this for the first time and it worked in the browser,

I felt something I didn’t feel since const/let/arrow functions

started to work natively in the browsers.

I hope you will enjoy it as well and have such feelings.

<pre><code>...</code></pre>tags in comments